- Home

- Heather Clark

Red Comet

Red Comet Read online

ALSO BY HEATHER CLARK

The Grief of Influence: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes

The Ulster Renaissance: Poetry in Belfast 1962–1972

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A.KNOPF

Copyright © 2020 by Heather Clark

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Clark, Heather L., author.

Title: Red comet : the short life and blazing art of Sylvia Plath / Heather Clark.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2020. | Identifiers: LCCN 2019041635 (print) | LCCN 2019041636 (ebook) | ISBN 9780307961167 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780307961174 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Plath, Sylvia. | Poets, American—20th century—Biography.

Classification: LCC PS3566.L27 Z616 2020 (print) | LCC PS3566.L27 (ebook) | DDC 811/.54—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041635

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041636

Ebook ISBN 9780307961174

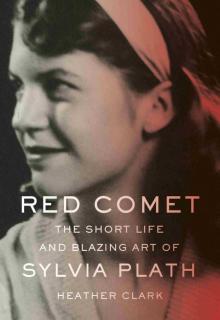

Cover photograph by Ramsey and Muspratt, Cambridge, UK Courtesy Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, USA

Cover design by John Gall

ep_prh_5.6.0_c0_r0

For Nathan, Isabel, and Liam

and

In Memory of Jon Stallworthy

…everyday, one has to earn the name of “writer” over again, with much wrestling.

—Sylvia Plath to Aurelia Plath, October 2, 1956

They thought death was worth it, but I

Have a self to recover, a queen.

Is she dead, is she sleeping?

Where has she been,

With her lion-red body, her wings of glass?

Now she is flying

More terrible than she ever was, red

Scar in the sky, red comet

Over the engine that killed her—

The mausoleum, the wax house.

—Sylvia Plath, “Stings”

Contents

Prologue

PART I

1. The Beekeeper’s Daughter

Prussia, Austria, America, 1850–1932

2. Do Not Mourn

Winthrop, 1932–1940

3. The Shadow

Wellesley, 1940–1945

4. My Thoughts to Shining Fame Aspire

Wellesley, 1946–1947

5. The Voice Within

Wellesley, 1947–1948

6. Summer Will Not Come Again

Wellesley, 1948–1950

7. The White Queen

Wellesley and Smith College, 1950–1951

8. Love Is a Parallax

Swampscott, Smith College, Cape Cod, 1951–1952

9. The Ninth Kingdom

Smith College, September 1952–May 1953

10. My Mind Will Split Open

Manhattan, June 1953

11. The Hanging Man

Wellesley, July–August 1953

12. Waking in the Blue

McLean Hospital, September 1953–January 1954

13. The Lady or the Tiger

Smith College and Harvard Summer School, January–August 1954

14. O Icarus

Smith College and Wellesley, September 1954–August 1955

PART II

15. Channel Crossing

Cambridge University, September 1955–February 1956

16. Mad Passionate Abandon

Cambridge University, February 1956

17. Pursuit

Cambridge and Europe, February–June 1956

18. Like Fury

Spain, Paris, Yorkshire, Cambridge, July–October 1956

19. Itched and Kindled

Cambridge University, October 1956–June 1957

20. In Midas’ Country

Cape Cod and Smith College, June 1957–June 1958

21. Life Studies

Northampton and Boston, June 1958–March 1959

22. The Development of Personality

Boston, America, Yaddo, April–December 1959

PART III

23. The Dread of Recognition

London, 1960

24. Nobody Can Tell What I Lack

London, January–March 1961

25. The Moment of the Fulcrum

London, March–August 1961

26. The Late, Grim Heart of Autumn

Devon, September–December 1961

27. Mothers

Devon, January–May 1962

28. Error

Devon, May–June 1962

29. I Feel All I Feel

Devon and London, June–August 1962

30. But Not the End

Devon and Ireland, August–September 1962

31. The Problem of Him

Devon and London, October 1962

32. Castles in Air

Devon and London, October–November 1962

33. Yeats’s House

London, December 1962–January 1963

34. What Is the Remedy?

London, January–February 1963

35. The Dark Ceiling

London, February 1963

Epilogue: Your Wife Is Dead

Postscript: A Poet’s Epitaph

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Notes on Sources

Notes

Illustration Credits

Prologue

In December 1962, Sylvia Plath moved into William Butler Yeats’s old house. Yeats was one of Plath’s greatest literary heroes, and she had been thrilled to discover the vacant townhouse in London’s Primrose Hill after the breakdown of her marriage. She was starting over, and she felt the move to Yeats’s house was propitious. “My work should be blessed,” she wrote her mother.1 She offered a year’s rent to secure the two-story maisonette—nearly all the money she had. Three months before, she and her husband, Ted Hughes, had traveled from their home in Devon to the west coast of Ireland, where they had collected apples from Yeats’s garden at Thoor Ballylee and climbed the famous winding staircase to his tower’s roof. Plath threw coins in the stream below for luck. The couple hoped that the trip to Ireland and the pilgrimage to Yeats’s sacred tower would rekindle their marriage. But Plath returned to Devon alone. There, and in Yeats’s house, she would write some of the finest poems of the twentieth century.

One of Sylvia Plath’s favorite short stories was Henry James’s “The Beast in the Jungle.” The story concerns a man, John Marcher, who spends his life waiting for an extreme experience—“the thing”—which he likens to a beast crouching in the jungle. It will be, he says, “natural” and “unmistakable.” It may be “violent,” a “catastrophe.” Only too late does Marcher realize he has lived a passionless existence awaiting the thing. He has instead become the man to

“whom nothing on earth was to have happened.” The story ends as he flings himself at the tomb of the woman he should have loved. “When the possibilities themselves had accordingly turned stale, when the secret of the gods had grown faint, had perhaps even quite evaporated, that, and that only, was failure,” James wrote. “It wouldn’t have been failure to be bankrupt, dishonoured, pilloried, hanged; it was failure not to be anything.”2

Sylvia Plath dreaded the prospect of such failure. In 1955, before setting off for England and Cambridge University, she wrote to her boyfriend Gordon Lameyer, “the horror, to be jamesian [sic], is to find there are plenty of beasts in the jungle but somehow to have missed all the potshots at them. I am always afraid of letting ‘life’ slip by unobtrusively and waking up some ‘fine morning’ to wail windgrieved around my tombstone.”3 Modernist visions of human paralysis terrified her. T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” and James Joyce’s “The Dead” became personal admonitions. “NEUTRALITY, BOREDOM become worse sins than murder, worse than illicit love affairs,” she told her Smith College students in 1958. “BE RIGHT OR WRONG, don’t be indifferent, don’t be NOTHING.”4 Plath’s appetite for food was legendary—she once emptied a host’s refrigerator before a dinner party—but she was equally hungry for experience. She was determined to live as fully as possible—to write, to travel, to cook, to draw, to love as much and as often as she could. She was, in the words of a close friend, “operatic” in her desires, a “Renaissance woman” molded as much by Romantic sublimity as New England stoicism.5 She was as fluent in Nietzsche as she was in Emerson; as much in thrall to Yeats’s gongs and gyres as Frost’s silences and snow.

Sylvia Plath took herself and her desires seriously in a world that often refused to do so. She published her first poem at age eight and later vowed to become “The Poetess of America.”6 In the years that followed, Plath pursued her literary vocation with a fierce, tireless determination. She hoped to be a writer, wife, and mother, but she was raised in a culture that openly derided female artistic ambition. Such derision is clear in the speech Democratic presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson gave at Plath’s 1955 Smith commencement, titled, “A Purpose for Modern Woman.” The best way these brilliant graduates could contribute to their nation, Stevenson said, was to embrace “the humble role of housewife, which, statistically, is what most of you are going to be whether you like the idea or not just now—and you’ll like it!” Stevenson, the liberal darling of his day, went on:

This assignment for you, as wives and mothers, has great advantages. In the first place, it is home work—you can do it in the living room with a baby in your lap, or in the kitchen with a can opener in your hands. If you’re really clever, maybe you can even practice your saving arts on that unsuspecting man while he’s watching television.

Stevenson acknowledged “the sense of contraction, the lost horizons” these women would feel in their new domestic roles. “Once they wrote poetry,” he mused. “Now it’s the laundry list….They had hoped to play their part in the crisis of the age. But what they do is wash diapers.” He hoped this view was not “too depressing” but concluded that “women ‘never had it so good’ as you do.”7

Plath was determined to play her part, but, as Stevenson’s speech suggests, the odds were against her. She lived in a shamelessly discriminatory age when it was almost impossible for a woman to get a mortgage, loan, or credit card; when newspapers divided their employment ads between men and women (“Attractive Please!”); the word “pregnant” was banned from network television; and popular magazines encouraged wives to remain quiet because, as one advice columnist put it, “his topics of conversation are more important than yours.”8 Government, finance, law, media, academia, medicine, technology, science—nearly all the professions were controlled by men. Some women made inroads, but the costs were high. As one of Plath’s Cambridge contemporaries wrote, women in the 1950s had “internalized from a lifetime of messages that achievement and autonomy were simply incompatible with love and family,” and that “independence equaled loneliness.”9 Still, Plath thought a different fate from the one Stevenson had predicted for her might be possible. Like her Joycean hero Stephen Dedalus, she was filled with “Icarian lust”: she would seek out her destiny abroad, collect experience for her art, and stay in motion.10 Anything to evade the life not lived, the poem not written, the love not realized. Plath spread her wings, over and over, at a time when women were not supposed to fly.

* * *

—

The Oxford professor Hermione Lee, Virginia Woolf’s biographer, has written, “Women writers whose lives involved abuse, mental-illness, self-harm, suicide, have often been treated, biographically, as victims or psychological case-histories first and as professional writers second.”11 This is especially true of Sylvia Plath, who has become cultural shorthand for female hysteria. When we see a female character reading The Bell Jar in a movie, we know she will make trouble. As the critic Maggie Nelson reminds us, “to be called the Sylvia Plath of anything is a bad thing.”12 Nelson reminds us, too, that a woman who explores depression in her art isn’t perceived as “a shamanistic voyager to the dark side, but a ‘madwoman in the attic,’ an abject spectacle.”13 Perhaps this is why Woody Allen teased Diane Keaton for reading Plath’s seminal collection Ariel in Annie Hall. In the 1980s, a prominent reviewer noted that a Plath “backlash” had resulted in some “grisly” jokes in college newspapers. “ ‘Why did SP cross the road?’ ‘To be struck by an oncoming vehicle.’ ”14 Male writers who kill themselves are rarely subject to such black humor: there are no dinner-party jokes about David Foster Wallace. In a 2017 article that went viral, Claire Dederer argued that Plath had become the culture’s ultimate “female monster” for committing suicide and “abandoning” her children.15 As the critic Carolyn Heilbrun noted, “If you admire Auden, that’s good taste. If you admire Sylvia Plath, it’s a cult….It is the usual no-win situation: either a woman author isn’t studied, or studying her is reduced to an act of misplaced religious fanaticism.”16

Since her suicide in 1963, Sylvia Plath has become a paradoxical symbol of female power and helplessness whose life has been subsumed by her afterlife. Caught in the limbo between icon and cliché, she has been mythologized and pathologized in movies, television, and biographies as a high priestess of poetry, obsessed with death. These distortions gained momentum in the 1960s when Ariel was published. Most reviewers didn’t know what to make of the burning, pulsating metaphors in poems like “Lady Lazarus” or the chilly imagery of “Edge.” Time called the book a “jet of flame from a literary dragon who in the last months of her life breathed a burning river of bale across the literary landscape.”17 The Washington Post dubbed Plath a “snake lady of misery” in an article entitled “The Cult of Plath.”18 Robert Lowell, in his introduction to Ariel, characterized Plath as Medea, hurtling toward her own destruction. Even Plath’s closest reader, her husband Ted Hughes, often portrayed her as a passive vessel through which a dangerous muse spoke.

Recent scholarship has deepened our understanding of Plath as a master of performance and irony.19 Yet the critical work done on Plath has not sufficiently altered her popular, clichéd image as the Marilyn Monroe of the literati. Melodramatic portraits of Plath as a crazed poetic priestess are still with us. A recent biographer called her “a sorceress who had the power to attract men with a flash of her intense eyes, a tortured soul whose only destiny was death by her own hand.” He wrote that she “aspired to transform herself into a psychotic deity.”20 These caricatures have calcified over time into the popular, reductive version of Sylvia Plath we all know: the suicidal writer of The Bell Jar whose cultish devotees are black-clad young women. (“Sylvia Plath: The Muse of Teen Angst,” reads the title of a 2003 article in Psychology Today.)21 Plath thought herself a different kind of “sorceress”: “I am a damn good high priestess of the intellect,” she wrote her friend Mel Woody in July 1954.22

&nbs

p; Many of Plath’s friends have grown impatient with these distorted versions of her. Plath’s close friend Phil McCurdy does not recognize the “literary psycho” he encounters in biographies that fail to capture her ebullient, brainy essence. “We were crazy, but it was crazy about Kafka,” he said.23 Plath’s Smith confidante Ellie Friedman Klein is tired of her brilliant friend being chained to “the death machine,” her suicide sensationalized.24 That Plath is now identified with the clichés she examined ironically in her work is part of her tragedy.

Elizabeth Hardwick once wrote of Sylvia Plath, “when the curtain goes down, it is her own dead body there on the stage, sacrificed to her own plot.”25 Yet to suggest that Plath’s suicide was some sort of grand finale only perpetuates the Plath myth that simplifies our understanding of her work and her life. Previous biographies have focused on the trajectory of Plath’s suicide, as if her every act, from childhood on, was predetermined to bring her closer to a fate she deserved for flying too close to the sun. This book will trace Plath’s literary and intellectual development rather than her undoing.

This is the first full biography of Sylvia Plath to incorporate all of her surviving letters—including fourteen newly discovered letters she sent to her psychiatrist in 1960–63 and several important unpublished letters—and to draw extensively on Plath’s unpublished diaries, calendars, and creative work in addition to her published writings. Because the Plath and Hughes estates allowed me to scan Plath’s and Hughes’s published and unpublished papers throughout this project, I have been able to quote directly from sources rather than hastily scribbled archival notes. This is also the first Plath biography to delve deeply into Plath’s family history, including her father’s FBI investigation and her grandmother’s institutionalization; to feature a surviving portion of Plath’s lost novel, Falcon Yard, which I discovered misfiled in an archive; to make use of previously unexamined police, court, and hospital records; to offer new interpretations and insights into Plath’s life based on the testimony and archival holdings of more than fifty contemporaries; to put forward new information that changes our understanding of Plath’s last week; and to draw on the entirety of Ted Hughes’s archives at Emory University and the British Library, which hold many unpublished poems and journal entries by Hughes about Plath. Lastly, this is the first biography of Plath to incorporate material from the Harriet Rosenstein archive at Emory University, which opened in 2020. Rosenstein interviewed scores of Plath’s contemporaries in the early 1970s while she was working on a Plath biography, which she never finished. These spectral voices from the past shed new light on Plath’s relationships, her medical treatment, and her writing.

Red Comet

Red Comet