- Home

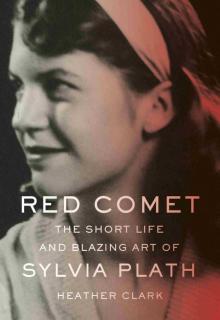

- Heather Clark

Red Comet Page 9

Red Comet Read online

Page 9

And make her frocks and aprons,

All trimmed in frills and lace.

I have to cook her breakfast,

And pet her when she’s ill;

And telephone the doctor

When Rebecca has a chill.

Rebecca doesn’t like that,

And says she’s well and strong;

And says she’ll try—oh! Very hard,

To be good all day long.

But when night comes, she’s nodding;

So into bed we creep

And snuggle up together

And soon are fast asleep.

I have no other dolly,

For you can plainly see,

In caring for Rebecca,

I’m busy as can be!54

When Sylvia herself became a mother, she would try to emulate this vision of “the angel in the house.” But she would rail against it as an artist.

An April 1939 letter shows Aurelia straddling the fine line between pressure and encouragement. She congratulated Sylvia for receiving all A’s on her report card, something that made her “a proud and happy mother.” She explained the concept of clay modeling and asked if Sylvia could find curves in pictures at her grandmother’s house: “In grandmother’s living room is the black and white picture of an old lady sitting in a chair. She is the mother of the man who made the picture. He made such wonderful pictures that he was called an artist. He loved his mother so much, that he made this picture of her.”55 Aurelia had unwittingly defined the concept of art as parental homage, an idea Plath later mocked in poems such as “The Disquieting Muses,” “Medusa,” “The Colossus,” and “Daddy.” Aurelia encouraged her daughter’s artistic leanings, but she could be prescriptive. Though she often wrote poems and drew pictures for Sylvia to color, sometimes her letters contained specific directives: “I am so proud of the fine coloring you are doing. Try to write as nicely as you color. Try to write words instead of printing them.”56

Sylvia’s own early letters from this time display a precocious ability with words and spelling; at age seven, she was writing in cursive and using correct grammar. Though her sentences are short, they possess a pleasing cadence that suggests an ear already tuned to lyricism. In late February 1940, she tried to make her father laugh, writing to him about a seagull that sat on an ice-cake: “Isn’t that funny (Ha Ha).” She reassured him that she was coming home soon, and asked, “Are you glad as I am?” But the bulk of this letter is about writing itself. She told her father that she got ink on her fingers that “never comes of! [sic].”57 Already she described the medium of writing as something that was of her, something permanent, but also a stain. A few months later, she sent Otto a Father’s Day card—his last—whose cover read, “My Heart Belongs to Daddy.” Inside, Sylvia wrote, “Happy Father’s Day” and “Raining Happiness” in neat cursive next to her drawing of an umbrella in the rain.58 The card was mailed from the Schobers’ house; Sylvia was away from home yet again.

A few early poems from this period survive. “My Mother and I,” “Snow,” “Pearls of Dew,” and probably “A-a-choo” and “Dover” date from 1940. Plath copied them, along with their dates of composition, into an illustrated notebook now held at the Morgan Library.59 She likely wrote them before her father’s death. At only seven and eight, she already understood the basic techniques of rhyme and iambic meter. “Dover,” for example, shows an assured use of the limerick form:

There was a young lady from Dover

Who happened to sit on some clover

The clover said, “Ow!”

She made it a bow, this queer young lady of Dover.

“A-a-choo” also draws on the limerick form. The poem is intriguing for its use of the phrase “achoo,” which would provide a baseline rhyme in “Daddy” many years later (“Barely daring to breathe or Achoo”). Critics have discussed the nursery rhyme cadences of “Daddy,” but Plath may have drawn on this earlier, half-remembered rhyme:

I saw a lady with a muff.

Her face was red as a powder puff.

She carried a big, big box of snuff.

That was made of every kind of stuff.

A-a-choo

Though these early poems are nonsensical, they show the young Sylvia delighting in formal rhyme and meter—and “queer” women.

Other poems from 1940 in the same notebook show similar experiments with rhyme and meter. In “My Mother and I,” Plath writes, “I love my mother / My mother loves me / And that is the way / That happy we be.” In the second stanza the poet claims that she would prefer “A hug or kiss” from her mother, rather than candy, as a reward for her good behavior. The poem consists of two quatrains with an a-b-c-b rhyme, and shows Plath discovering iambic and dactylic meter. “Pearls of Dew (Chant),” in its variations and assured use of caesurae, achieves a relative sophistication that Plath’s other 1940 poems lack:

In the early morning

When the dawn is breaking,

Lacy cobweb scarves lie

Strewn amongst the grass,

Jeweled with pearly dew;

Fairies must have used them

Dancing ’neath the moon.

The influence of children’s fairy tales is obvious here, but the voice of William Butler Yeats, whom Aurelia had read to Sylvia as a toddler, is also present. “Pearls of Dew” and other juvenilia show that Plath had begun assimilating Yeats’s influence very early.

Another of the 1940 notebook poems is simply titled “Snow.” Three different versions of this poem exist in early notebooks, suggesting that at an extremely young age Plath was beginning to experiment with revision. The first stanza of the earliest version reads:

Snow, Snow sifting down

Sifting quietly ’round the town

Sending it a blanket of cold white

To keep it warm every night.

Snow, Snow

Sifting down

Sifting quietly ’round the town.

“Snow” is sentimental in the manner of a Currier and Ives print, yet its evocation of a town muffled within cold white depths is not strictly childlike; it suggests a familiar mournful element present in Plath’s later works that depict white, frozen imagery. As in the famous ending of James Joyce’s “The Dead,” the snow both protects and entombs. The precocious young poet likely delighted in her paradoxical imagery—the blanket of cold snow keeping the town warm—as well as her use of repetition to achieve perfect trochaic tetrameter in the first stanza’s last line. She had not yet learned formal metric terms and rules, but they came to her naturally.

Biographers have used the trope of addiction to describe Plath’s literary ambition, writing that she was “addicted to achievement in the same way an alcoholic is hooked on booze.” Or that her “competitive drive” was “pathological” and stemmed from “interior hollowness.”60 Such rhetoric trivializes Plath’s commitment to her academic success and her literary vocation. (Male ambition is rarely described in this way.) These very early poems, and perhaps many others that have not survived, suggest that the origins of her art were not rooted in trauma or supplication, but in confidence, pleasure, and self-satisfaction. Writing was not something Sylvia did to please others, but to please herself—as necessary as breathing, as she would later remark in a 1962 interview.

* * *

ON A SUMMER MORNING in 1940, Otto stubbed his toe on his dresser while getting ready to teach. By the time he arrived home late that afternoon, it had turned black. Aurelia invited a doctor into the house on the pretext of examining the children.61 The doctor surreptitiously examined Otto’s urine, which revealed he did not have lung cancer but diabetes—a condition that could have been managed with insulin treatments had it been caught in time. But it had not been caught in time, and Otto Plath died less than three mont

hs later.

Plath has written about feeling “sealed off” from her childhood when her family left Winthrop for Wellesley, but she was also sealed off, at her grandparents’ house, from her father’s illness and her mother’s struggles. Sylvia sensed the severity of the crisis during the late summer of 1940, when she asked to remain at home to help care for her father alongside the visiting nurse. As Aurelia recalled, “the friendly nurse cut down an old uniform for her and called Sylvia her ‘assistant,’ who could bring Daddy fruit or cool drinks now and then, along with the drawings she made for him, which gave him some cheer.”62 A photograph from this time shows Sylvia outside in her nurse’s uniform, complete with apron and hat, smiling as she tends a baby doll. She later pasted this photo in her scrapbook. In her 1959 poem “The Colossus,” a lonely, exiled daughter—half nun, half nurse—remains a caretaker to her father’s monumental corpus statue.

Plath rendered this time in her autobiographical story “Among the Bumblebees,” written during the fall of 1954. The protagonist, Alice Denway, describes her entomologist father as “proud and arrogant,” a Nietzschean demi-god. Alice’s mother, based on Aurelia, is “tender and soft like the Madonna pictures in Sunday school.” Alice does not want to be tender and soft; she wants to be “strong and superior” like her father, who “did not like anyone to cry.” Unlike her little brother, Warren (Plath used her brother’s real name in the story), who is asthmatic and coddled, Alice is full of vitality and strength, able to withstand the full brunt of the sun that burns Warren’s skin. Alice and her father make up the strong team, her mother and brother the weak one.

Alice learned to sing the thunder song with her father: “Thor is angry. Thor is angry. Boom, boom, boom! Boom, boom, boom! We don’t care. We don’t care. Boom, boom, boom!” And above the resonant resounding baritone of her father’s voice, the thunder rumbled harmless as a tame lion….The swollen purple and black clouds broke open with blinding flashes of light, and the thunderclaps made the house shudder to the root of its foundations. But with her father’s strong arms around her and the steady reassuring beat of his heart in her ears, Alice believed that he was somehow connected with the miracle of fury beyond the windows, and that through him, she could face the doomsday of the world in perfect safety.63

In truth, it was Aurelia who sang the “thunder song” to the children and soothed them during the hurricane of ’38.64 Yet in the story, it is the ghostly father who protects, who would always embody the Gothic sublimity of raging storms.

As Otto’s health deteriorated, he became too weak to teach effectively. Aurelia hired someone to help with household chores during the day, then spent her evenings reading through Otto’s biology and entomology books, “abstracting material to update his lectures, correcting German quizzes, and attending to his correspondence.”65 The Germanic values of order, stoicism, obedience, and hard work had morphed, in extremity, into a coping mechanism akin to denial; self-pity was a weakness not to be tolerated. Plath’s later fetishization of health, strength, and vigor were likely rooted in her parents’ conspiratorial denial of illness, which she witnessed as a girl.

But the time came when the truth could no longer be ignored. Soon after receiving his diabetes diagnosis, Otto contracted pneumonia and spent two weeks in the hospital. He returned home with a full-time nurse, an expense that added to the growing pile of medical bills (he had no health insurance). On the nurse’s first day off, he suggested that Aurelia take the children to the beach for the afternoon. She did so, reluctantly, and returned to find her husband collapsed on the stairs. He was, according to Aurelia, “a fanatical gardener” and had mustered all his strength to plant bulbs in his yard.66 Another doctor was summoned, Dr. Loder, who declared Otto’s foot gangrened; the whole leg would have to be amputated. As the doctor left, he muttered, “How could such a brilliant man be so stupid.”67

The amputation was performed on October 12, 1940, about two weeks before Sylvia’s eighth birthday. The Boston University community rallied to lift Otto’s spirits: colleagues covered his classes, former students donated blood, and the university president wrote, “We’d rather have you back at your desk with one leg than any other man with two.”68 But Otto fell into a depression after the surgery and refused to discuss learning to walk with a prosthesis. At 9:35 p.m. on November 5, 1940, shortly after Aurelia returned home from the hospital, he died of an embolism in the lung. The official cause of death was listed as diabetes mellitus and bronchial pneumonia, due to gangrene in the left foot.69 During his last few hours alive, Otto said to Aurelia, “I don’t mind the thought of death at all, but I would like to see how the children grow up.”70

In Letters Home, Aurelia’s story of Otto’s illness is determinedly straightforward; duty and sacrifice animate the memoir rather than unseemly feelings of anger, guilt, or grief. Only once does Aurelia hint at her agony:

In the middle of the night he called me and I found him feverish, shaking from head to foot with chills, his bed clothes soaked with perspiration. All the rest of that night I kept changing sheets, sponging his face, and holding his trembling hands. At one point he caught my hands, and holding on, said hoarsely, “God knows, why I have been so cussed!” As tears streamed down my face, I could only think, “All this needn’t have happened; it needn’t have happened.”71

If Aurelia had disobeyed her husband and found a doctor willing to treat the reluctant patient, Otto might have lived. Later, Sylvia would secretly blame Aurelia for standing by while Otto committed what she saw as his slow suicide. Otto became, as Sylvia’s college boyfriend Richard Sassoon remembered, “a highly charged legend for her.”72

* * *

AURELIA WAITED UNTIL the morning to tell the children that Otto had died. She found Sylvia already awake and reading in her bed. “She looked at me sternly for a moment, then said woodenly, ‘I’ll never speak to God again!’ I told her that she did not need to attend school that day if she’d rather stay at home. From under the blanket she had pulled over her head came her muffled voice, ‘I want to go to school.’ ”73 Sylvia’s reaction demonstrated equal measures of rebellion and conformity—the very traits that continued to drive her behavior throughout the rest of her life. In the young girl’s rejection of God, there is an echo of the bold, assertive Ariel voice that would later mock patriarchal ideologies and symbols of power. That voice dates to this moment of rupture. Yet, in a pivot that would become increasingly habitual, she composed herself for her schoolfellows, perhaps seeking solace and connection in the ordinary. But it was a difficult day for Sylvia, who came home from school crying and upset. There were playground taunts about the prospect of a stepfather. That afternoon Sylvia made Aurelia sign a note promising she would never remarry, which for years she kept folded in the back of her diary. Aurelia kept her promise, though she later assured her daughter the decision had nothing to do with her vow.

On the afternoon of November 9, Otto was buried on Azalea Path in Winthrop’s town cemetery. Aurelia and her family, as well as friends and colleagues from Boston University, attended his funeral at Winthrop’s United Methodist Church. Aurelia kept the children home. A brief obituary ran in the Winthrop Review and The Boston Globe. Otto’s colleagues at Boston University published a moving tribute to him in the university magazine, citing the international impact of Bumblebees and Their Ways and recalling his “loyalty to the highest ideals of science, his genuine frankness in discussion of any subject, and the sincerity of his beliefs….His generous, sincere, and energetic nature won him a lasting place in the affection and regard of those privileged to work with him.” The university had lost “a worthy teacher and a great scholar.”74 Otto’s gravestone, number 1123, was a modest slab laid flat on the ground. Years later, when Sylvia finally visited the grave, she would have difficulty locating it. The small stone angered her, but Aurelia insisted that Otto would have wanted something unassuming. Besides, he did not have a pension, and mo

st of his small life insurance policy of $5,000 went to medical bills and funeral costs. There was no money for a larger memorial.

Aurelia’s stoicism in the face of Otto’s death implied that personal tragedy was not something to be indulged. One had to move on; one could not yield. In The Bell Jar, Plath wrote of Esther Greenwood,

Then I remembered I had never cried for my father’s death.

My mother hadn’t cried either. She had just smiled and said what a merciful thing it was for him he had died, because if he had lived he would have been crippled and an invalid for life, and he couldn’t have stood that, he would rather have died than had that happen.75

Aurelia claimed that concern for her children’s fragile emotional state caused her to hide her grief, and keep them away from their father’s funeral.

What I intended as an exercise in courage for the sake of my children was interpreted years later by my daughter as indifference. “My mother never had time to mourn my father’s death.” I had vividly remembered a time when I was a little child, seeing my mother weep in my presence and feeling that my whole personal world was collapsing. Mother, the tower of strength, my one refuge, crying! It was this recollection that compelled me to withhold my tears until I was alone in bed at night.76

As a Wellesley neighbor and family friend remembered, “There was no dwelling upon its effects….If the going was difficult at home, there was no complaining.”77

Aurelia was the sole breadwinner now. “Here I was, a widow with two young children to support. I had a man’s responsibilities, but I was making a single woman’s salary.”78 She began substitute teaching for $25 a week at Braintree High School, where she taught three German classes and two Spanish classes each day; her commute necessitated a predawn departure. Aurelia’s parents moved in to help with child care. Resolutely pragmatic, Aurelia tried to make the best of a tragedy. Her parents were “healthy, optimistic, strong in their faith, and loved the children dearly. My young brother, only thirteen years Sylvia’s senior, and my sister would be close to us—the children would have a sense of family and be surrounded with care and love.”79 But Otto’s death was financially and emotionally devastating for the small family. Sylvia later told Dr. Beuscher that from then on Aurelia was a “beaten down woman constantly emphasizing poverty and sacrifice for intellect.”80

Red Comet

Red Comet